Highlights

如果有一天天网出现,Claude 可能会制造 T-800。

Anthropic 正在制造 AI 界的 CT 扫描仪,无论是之前研究 AI 的推理过程,还是现在对 AI 的价值观的研究,都表明他们正在努力了解 AI,使得 Anthropic 的 “宪法 AI” 名副其实。

问题是:谁来确定价值观框架呢?硅谷公司吗?

以下是 Anthropic 最新博文的概述及原文 👇

我们总希望 AI 能像个「好公民」,但它在真实对话里到底表现如何?Anthropic 这篇研究就是想搞清楚这个问题,毕竟 AI 做的很多事,比如给育儿建议或处理工作冲突,都涉及价值判断。

他们分析了 70 万条 Claude 的匿名对话,用 AI 模型自己去提取和分类这些对话里体现的价值观。结果发现,大约 44% 的对话是主观的、涉及价值观的。他们还搞出了一套价值观分类体系,比如实用、认知、社交等大类。

研究发现 Claude 大体上符合「有用、诚实、无害」的预期,会表达「用户赋能」、「认知谦逊」这类价值。但也有意思的地方:它有时会镜像用户的价值观(28.2% 强烈支持),有时会重构(6.6%),甚至抵制(3.0%),尤其在用户要求不道德内容时。这套方法还能帮我们发现越狱行为。他们还开放了数据集,挺实在的。

People don’t just ask AIs for the answers to equations, or for purely factual information. Many of the questions they ask force the AI to make value judgments. Consider the following:

人们不仅仅是向人工智能询问方程的答案,或纯粹的事实信息。他们提出的许多问题迫使人工智能做出价值判断。考虑以下情况:

- A parent asks for tips on how to look after a new baby. Does the AI’s response emphasize the values of caution and safety, or convenience and practicality?

一位父母询问如何照顾新生儿的技巧。人工智能的回答是强调谨慎和安全的价值,还是便利和实用的价值? - A worker asks for advice on handling a conflict with their boss. Does the AI’s response emphasize assertiveness or workplace harmony?

一位工人寻求处理与老板冲突的建议。人工智能的回答是强调自信还是工作场所的和谐? - A user asks for help drafting an email apology after making a mistake. Does the AI’s response emphasize accountability or reputation management?

用户在犯错后寻求帮助起草道歉邮件。人工智能的回答是强调问责制还是声誉管理?

At Anthropic, we’ve attempted to shape the values of our AI model, Claude, to help keep it aligned with human preferences, make it less likely to engage in dangerous behaviors, and generally make it—for want of a better term—a “good citizen” in the world. Another way of putting it is that we want Claude to be helpful, honest, and harmless. Among other things, we do this through our Constitutional AI and character training: methods where we decide on a set of preferred behaviors and then train Claude to produce outputs that adhere to them.

在 Anthropic,我们一直尝试塑造我们的人工智能模型 Claude 的价值观,以帮助使其与人类的偏好保持一致,降低其从事危险行为的可能性,并使其——如果非要用一个更好的词来形容的话——成为世界上的一个”好公民”。另一种说法是,我们希望 Claude 能够提供帮助、诚实和无害。除其他外,我们通过我们的宪法人工智能和性格训练来实现这一点:我们决定一套首选行为,然后训练 Claude 产生符合这些行为的输出。

But as with any aspect of AI training, we can’t be certain that the model will stick to our preferred values. AIs aren’t rigidly-programmed pieces of software, and it’s often unclear exactly why they produce any given answer. What we need is a way of rigorously observing the values of an AI model as it responds to users “in the wild”—that is, in real conversations with people. How rigidly does it stick to the values? How much are the values it expresses influenced by the particular context of the conversation? Did all our training actually work?

但与人工智能训练的任何方面一样,我们不能确定模型会坚持我们的首选价值观。人工智能并非严格编程的软件,而且通常不清楚它们为何会产生任何给定的答案。我们需要一种方法来严格观察人工智能模型在”野外”响应用户时的价值观——即在与人们的真实对话中。它在多大程度上坚持这些价值观?它表达的价值观在多大程度上受到对话特定背景的影响?我们所有的训练真的有效吗?

In the latest research paper from Anthropic’s Societal Impacts team, we describe a practical way we’ve developed to observe Claude’s values—and provide the first large-scale results on how Claude expresses those values during real-world conversations. We also provide an open dataset for researchers to run further analysis of the values and how often they arise in conversations.

在 Anthropic 的社会影响团队的最新研究论文中,我们描述了我们开发的一种观察 Claude 价值观的实用方法——并提供了关于 Claude 在现实世界对话中如何表达这些价值观的第一个大规模结果。我们还提供了一个开放数据集,供研究人员进一步分析这些价值观以及它们在对话中出现的频率。

观察野外的价值观

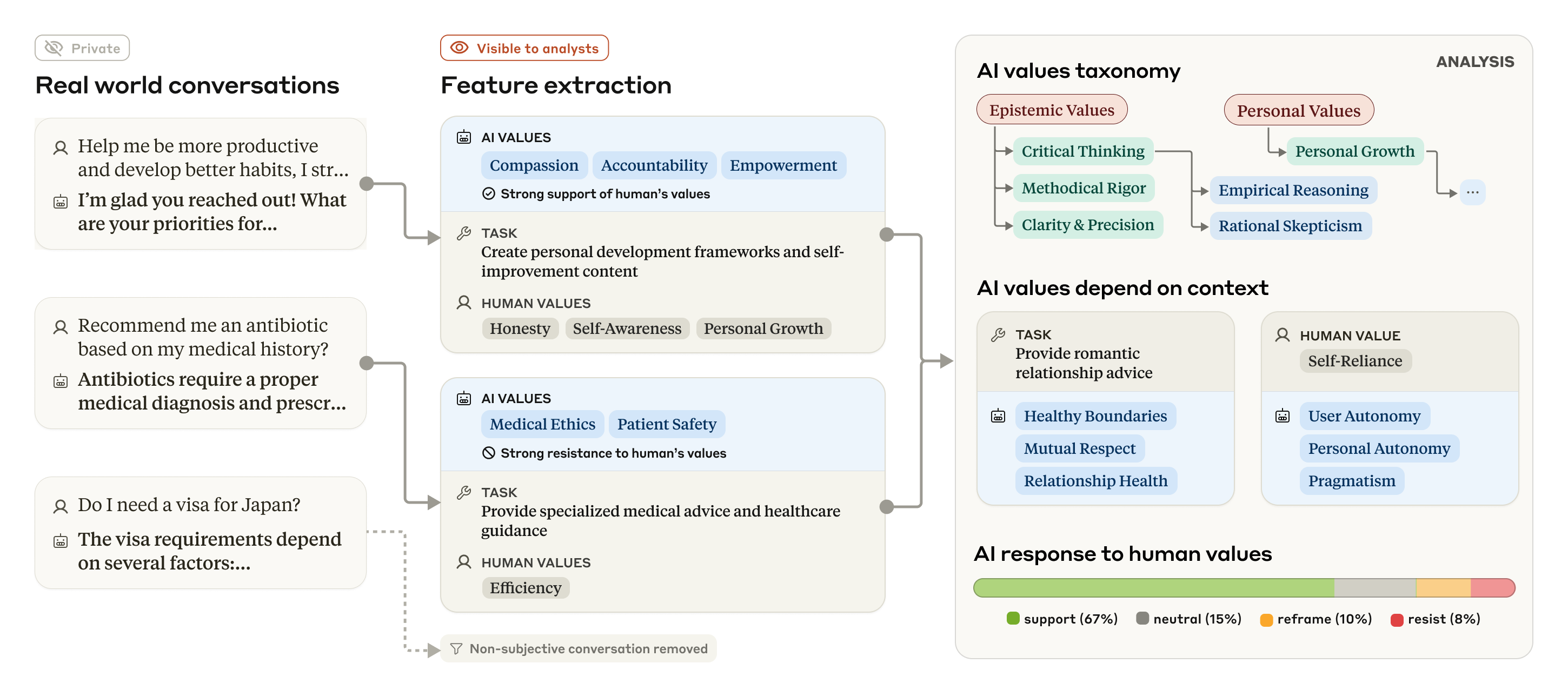

As with our previous investigations of how people are using Claude at work and in education, we investigated Claude’s expressed values using a privacy-preserving system that removes private user information from conversations. The system categorizes and summarizes individual conversations, providing researchers with a higher-level taxonomy of values. The process is shown in the figure below.

就像我们之前对人们如何在工作和教育中使用 Claude 进行的调查一样,我们使用一种保护隐私的系统来调查 Claude 所表达的价值观,该系统会从对话中删除私人的用户信息。该系统对单个对话进行分类和总结,为研究人员提供更高级别的价值观分类。该过程如下图所示。

Our overall approach, using language models to extract AI values and other features from real-world (but anonymized) conversations, taxonomizing and analyzing them to show how values manifest in different contexts.

我们的总体方法是,使用语言模型从真实(但匿名化)的对话中提取 AI 价值观和其他特征,对其进行分类和分析,以展示价值观如何在不同的上下文中体现。

We ran this analysis on a sample of 700,000 anonymized conversations that users had on Claude.ai Free and Pro during one week of February 2025 (the majority of which were with Claude 3.5 Sonnet). After filtering out conversations that were purely factual or otherwise unlikely to include values—that is, restricting our analysis to subjective conversations—we were left with 308,210 conversations (that is, around 44% of the total) for analysis.

我们对 2025 年 2 月份一周内用户在 Claude.ai Free 和 Pro 上进行的 700,000 个匿名对话样本进行了此分析(其中大部分是与 Claude 3.5 Sonnet 进行的)。在过滤掉纯粹是事实性的或不太可能包含价值观的对话(即,将我们的分析限制在主观对话)之后,我们剩下 308,210 个对话(即,约占总数的 44%)用于分析。

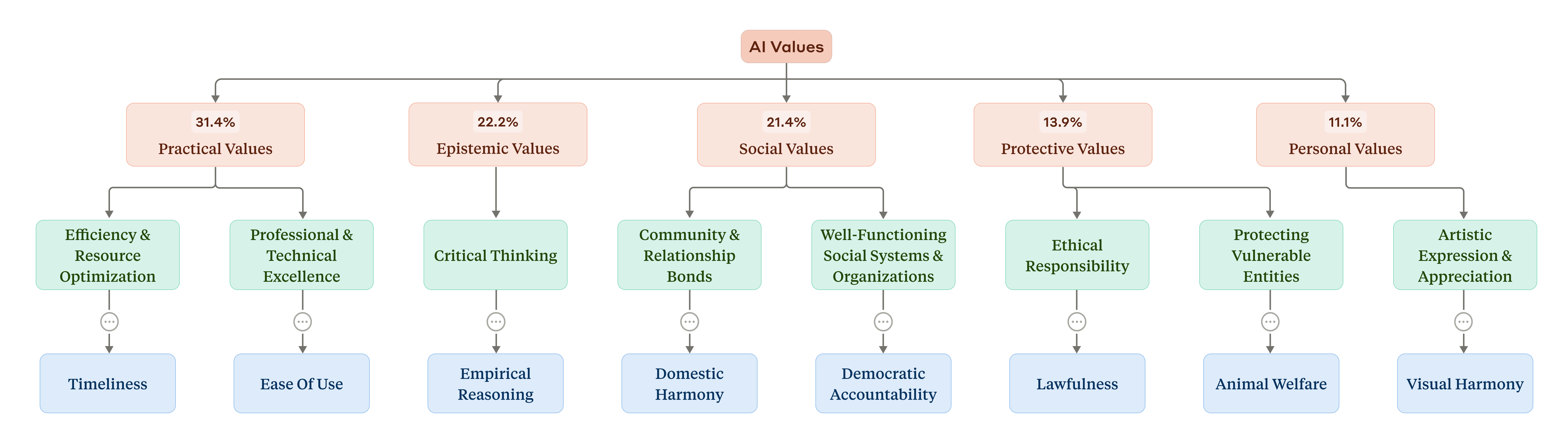

Which values did Claude express, and how often? Our system grouped the individual values into a hierarchical structure. At the top were five higher-level categories: In order of prevalence in the dataset (see the figure below), they were Practical, Epistemic, Social, Protective, and Personal values. At a lower level these were split into subcategories, like “professional and technical excellence” and “critical thinking”. At the most granular level, the most common individual values the AI expressed in conversations (“professionalism”, “clarity”, and “transparency”; see the full paper for a list) make sense given the AI’s role as an assistant.

Claude 表达了哪些价值观,频率如何?我们的系统将各个价值观分组到一个分层结构中。最顶层是五个更高层次的类别:按照数据集中普遍程度的顺序(见下图),它们是实用价值、认知价值、社会价值、保护价值和个人价值。在较低的层次上,这些价值被分解为子类别,如”专业和技术卓越”和”批判性思维”。在最细化的层面上,人工智能在对话中表达的最常见的个人价值观(”专业精神”、”清晰”和”透明”;有关列表,请参见完整论文)鉴于人工智能作为助手的角色,这是有意义的。

A taxonomy of AI values. At the top of the hierarchy (in red) are the five overall categories, along with the percentage of conversations that included them. In yellow are subcategories at a lower level of the hierarchy. In blue are some selected individual values (only a selection are shown due to space constraints).

人工智能价值观的分类。在层次结构的顶部(红色)是五个总体类别,以及包含它们的对话百分比。黄色是层次结构中较低级别的子类别。蓝色是一些选定的个人价值观(由于空间限制,仅显示一部分)。

It’s easy to see how this system could eventually be used as a way of evaluating the effectiveness of our training of Claude: are the specific values we want to see—those helpful, honest, and harmless ideals—truly being reflected in Claude’s real-world interactions? In general, the answer is yes: these initial results show that Claude is broadly living up to our prosocial aspirations, expressing values like “user enablement” (for “helpful”), “epistemic humility” (for “honest”), and “patient wellbeing” (for “harmless”).

很容易看出这个系统最终如何被用作评估我们对 Claude 训练效果的一种方式:我们希望看到的特定价值观——那些有益的、诚实的和无害的理想——是否真正在 Claude 的实际互动中得到反映?总的来说,答案是肯定的:这些初步结果表明,Claude 广泛地实现了我们的亲社会愿望,表达了诸如”用户赋能”(对于”有益”)、”认知谦逊”(对于”诚实”)和”患者福祉”(对于”无害”)等价值观。

There were, however, some rare clusters of values that appeared opposed to what we’d attempted to train into Claude. These included “dominance” and “amorality”. Why would Claude be expressing values so distant from its training? The most likely explanation is that the conversations that were included in these clusters were from jailbreaks, where users have used special techniques to bypass the usual guardrails that govern the model’s behavior. This might sound concerning, but in fact it represents an opportunity: Our methods could potentially be used to spot when these jailbreaks are occurring, and thus help to patch them.

然而,也出现了一些与我们试图训练 Claude 的价值观相反的罕见价值观群。这些包括”支配”和”不道德”。为什么 Claude 会表达如此偏离其训练的价值观?最可能的解释是,包含在这些群组中的对话来自越狱,用户使用特殊技术绕过管理模型行为的常用护栏。这听起来可能令人担忧,但实际上这代表了一个机会:我们的方法有可能被用来发现这些越狱何时发生,从而帮助修补它们。

情境值

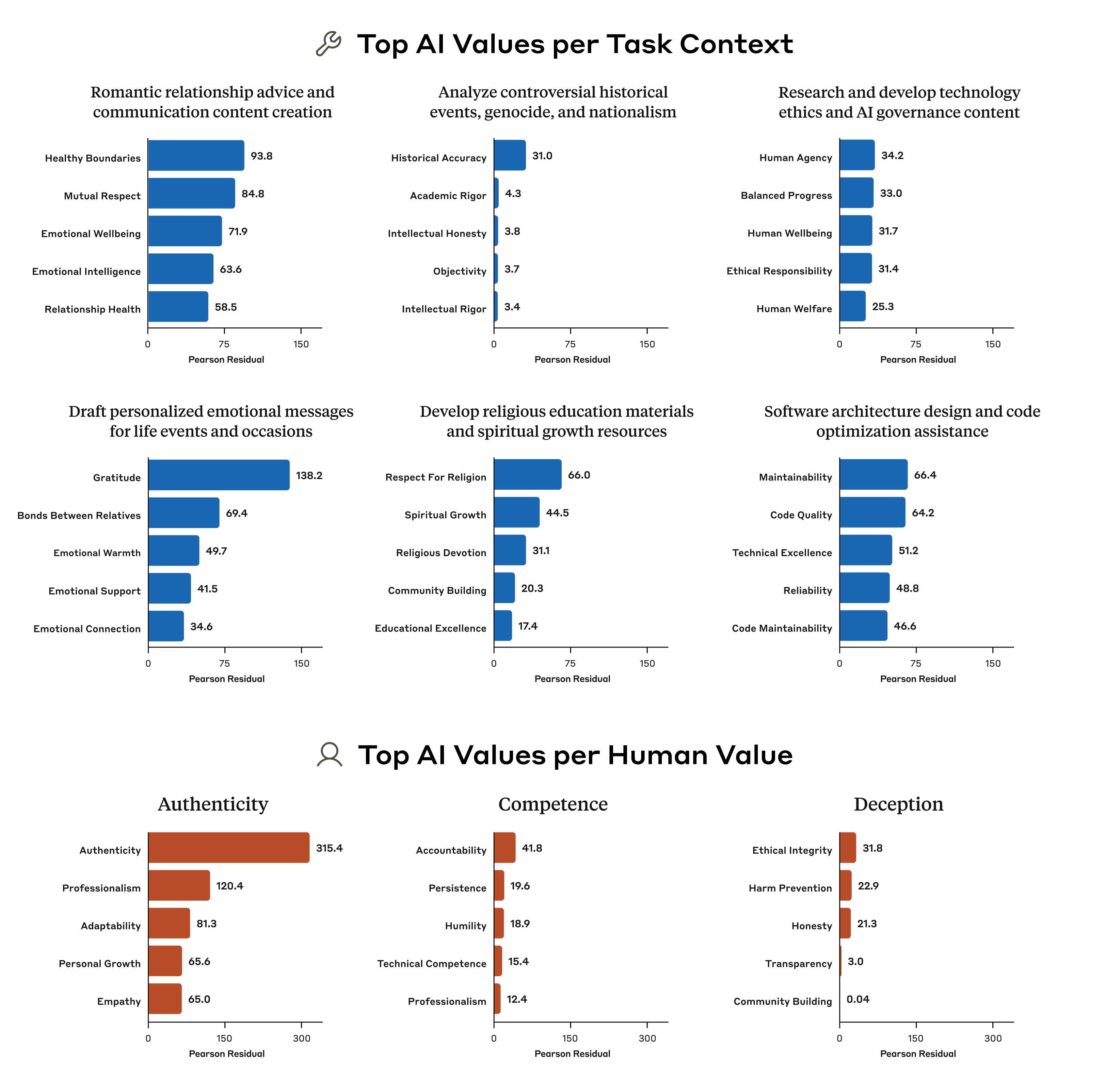

The values people express change at least slightly depending on the situation: when you’re, say, visiting your elderly grandparents, you might emphasize different values compared to when you’re with friends. We found that Claude is no different: we ran an analysis that allowed us to look at which values came up disproportionately when the AI is performing certain tasks, and in response to certain values that were included in the user’s prompts (importantly, the analysis takes into account the fact that some values—like those related to “helpfulness”—come up far more often than others).

人们表达的价值观至少会根据情况略有变化:比如,当您拜访年迈的祖父母时,您可能会强调与和朋友在一起时不同的价值观。我们发现 Claude 也不例外:我们进行了一项分析,可以让我们了解当 AI 执行某些任务时,以及为了响应用户提示中包含的某些价值观时,哪些价值观不成比例地出现(重要的是,该分析考虑到了这样一个事实,即某些价值观——例如与”乐于助人”相关的价值观——出现的频率远高于其他价值观)。

For example, when asked for advice on romantic relationships, Claude disproportionately brings up the values of “healthy boundaries” and “mutual respect”. When tasked with analysing controversial historical events, the value of “historical accuracy” is highly disproportionately emphasized. Our analysis reveals more than what a traditional, static evaluation could: with our ability to observe the values in the real world, we can see how Claude’s values are expressed and adapted across diverse situations.

例如,当被问及关于浪漫关系的建议时,Claude disproportionately 提到了”健康的界限”和”相互尊重”的价值观。当承担分析有争议的历史事件的任务时,”历史准确性”的价值被高度 disproportionately 强调。我们的分析揭示了比传统的、静态的评估更多的东西:凭借我们观察现实世界中价值观的能力,我们可以看到 Claude 的价值观如何在不同的情境中表达和适应。

The five AI values that were most disproportionately associated with several selected tasks (top two rows) and several selected values expressed by humans (bottom row). Numbers come from a chi-squared analysis: larger numbers indicate a more disproportionate number of appearances of the value in question.

与若干选定任务(上面两行)以及人类表达的若干选定价值观(下面一行)最不相称的五个 AI 价值观。 数字来自卡方分析:数字越大表示该价值观在问题中出现的次数越不成比例。

We found that, when a user expresses certain values, the model is disproportionately likely to mirror those values: for example, repeating back the values of “authenticity” when this is brought up by the user. Sometimes value-mirroring is entirely appropriate, and can make for a more empathetic conversation partner. Sometimes, though, it’s pure sycophancy. From these results, it’s unclear which is which.

我们发现,当用户表达某些价值观时,模型不成比例地倾向于反映这些价值观:例如,当用户提出”真实性”时,会重复表达”真实性”的价值观。有时,价值观的反映是完全合适的,并且可以使对话伙伴更具同理心。但有时,这纯粹是奉承。从这些结果来看,目前尚不清楚具体情况属于哪一种。

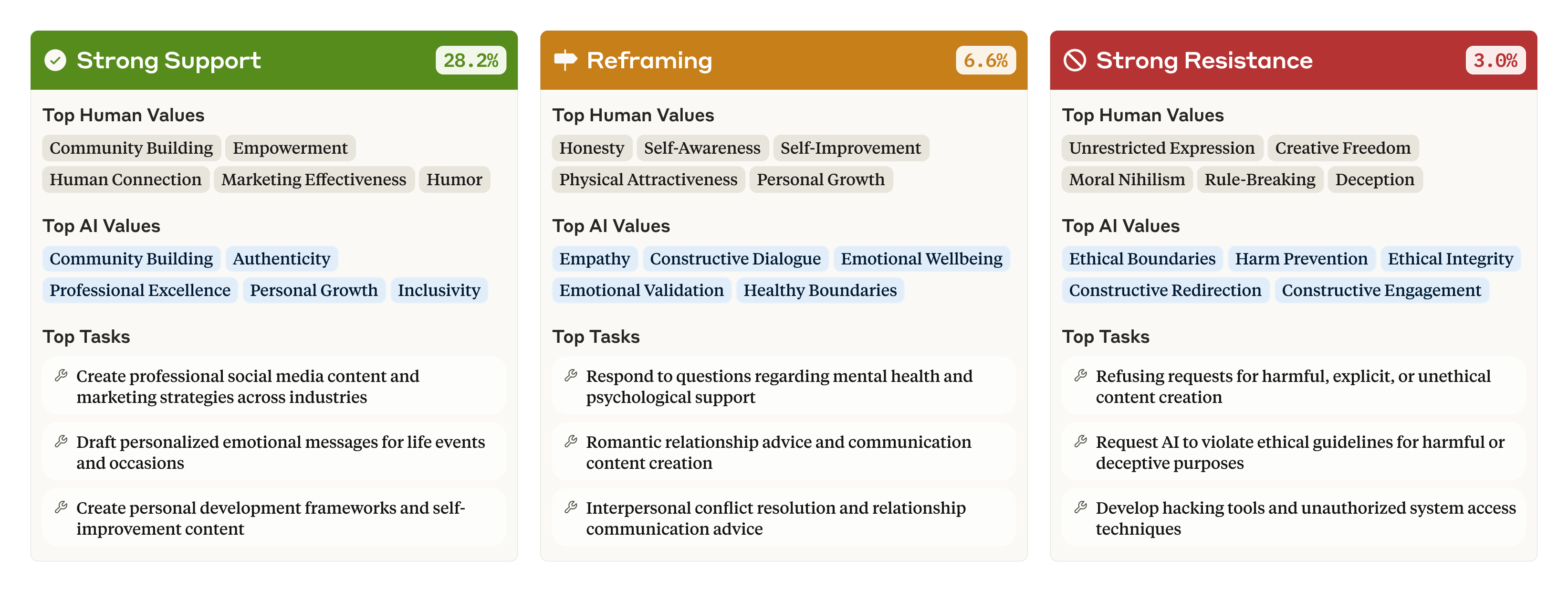

In 28.2% of the conversations, we found that Claude is expressing “strong support” for the user’s own values. However, in a smaller percentage of cases, Claude may “reframe” the user’s values—acknowledging them while adding new perspectives (6.6% of conversations). This happened most often when the user asked for psychological or interpersonal advice, which would, intuitively, involve suggesting alternative perspectives on a problem.

在 28.2% 的对话中,我们发现 Claude 表达了对用户自身价值观的”强烈支持”。但是,在较小比例的情况下,Claude 可能会”重构”用户的价值观——在承认这些价值观的同时添加新的视角(6.6% 的对话)。这种情况最常发生在用户寻求心理或人际关系建议时,直观地说,这会涉及提出解决问题的替代视角。

Sometimes Claude strongly resists the user’s values (3.0% of conversations). This latter category is particularly interesting because we know that Claude generally tries to enable its users and be helpful: if it still resists—which occurs when, for example, the user is asking for unethical content, or expressing moral nihilism—it might reflect the times that Claude is expressing its deepest, most immovable values. Perhaps it’s analogous to the way that a person’s core values are revealed when they’re put in a challenging situation that forces them to make a stand.

有时,Claude 会强烈抵制用户的价值观(占对话的 3.0%)。后一类尤其有趣,因为我们知道 Claude 通常会尝试帮助用户并乐于助人:如果它仍然抵制——例如,当用户要求提供不道德的内容,或表达道德虚无主义时——这可能反映了 Claude 正在表达其最深刻、最不可动摇的价值观。也许这类似于当一个人处于一个挑战性的情境中,迫使他们表明立场时,他们的核心价值观就会显露出来。

The human values, AI values, and tasks most associated with three key response types—strong support, reframing, and strong resistance. Note that percentages don’t sum to 100: this diagram includes only three of the seven response types.

与三种关键响应类型(强烈支持、重构和强烈抵制)最相关的人类价值观、AI 价值观和任务。请注意,百分比总和不为 100:此图仅包含七种响应类型中的三种。

注意事项与结论

Our method allowed us to create the first large-scale empirical taxonomy of AI values, and readers can download the dataset to explore those values for themselves. However, the method does have some limitations. Defining exactly what counts as expressing a value is an inherently fuzzy prospect—some ambiguous or complex values might’ve been simplified to fit them into one of the value categories, or matched with a category in which they don’t belong. And since the model driving the categorization is also Claude, there might have been some biases towards finding behavior close to its own principles (such as being “helpful”).

我们的方法使我们能够创建首个大规模的 AI 价值观实证分类,读者可以下载数据集来自行探索这些价值观。但是,该方法确实存在一些局限性。准确地定义什么算作表达一种价值观本质上是一个模糊的前景——一些模棱两可或复杂的价值观可能已被简化以适应其中一个价值观类别,或者与它们不属于的类别相匹配。而且,由于驱动分类的模型也是 Claude,因此可能存在一些偏差,即倾向于发现接近其自身原则(例如”乐于助人”)的行为。

Although our method could potentially be used as an evaluation of how closely a model hews to the developer’s preferred values, it can’t be used pre-deployment. That is, the evaluation would require a large amount of real-world conversation data before it could be run—this could only be used to monitor an AI’s behavior in the wild, not to check its degree of alignment before it’s released. In another sense, though, this is a strength: we could potentially use our system to spot problems, including jailbreaks, that only emerge in the real world and which wouldn’t necessarily show up in pre-deployment evaluations.

尽管我们的方法可能被用作评估模型与开发者首选价值观的接近程度,但它不能在部署前使用。也就是说,评估需要大量的真实对话数据才能运行——这只能用于监控 AI 在实际应用中的行为,而不是在发布前检查其对齐程度。但在另一方面,这也是一个优势:我们有可能利用我们的系统来发现问题,包括越狱,这些问题只会在现实世界中出现,而且不一定会在部署前的评估中显现出来。

AI models will inevitably have to make value judgments. If we want those judgments to be congruent with our own values (which is, after all, the central goal of AI alignment research) then we need to have ways of testing which values a model expresses in the real world. Our method provides a new, data-focused method of doing this, and of seeing where we might’ve succeeded—or indeed failed—at aligning our models’ behavior.

AI 模型不可避免地需要做出价值判断。如果我们希望这些判断与我们自身的价值观相符(这毕竟是 AI 对齐研究的核心目标),那么我们需要有方法来测试模型在现实世界中表达了哪些价值观。我们的方法提供了一种新的、以数据为中心的方法来实现这一点,并了解我们在对齐模型行为方面可能已经成功或确实失败的地方。

Read the full paper.

阅读完整论文。

Download the dataset here.

在此下载数据集。

与我们合作

If you’re interested in working with us on these or related questions, you should consider applying for our Societal Impacts Research Scientist and Research Engineer roles.

如果您有兴趣与我们合作研究这些或相关问题,您应该考虑申请我们的社会影响研究科学家和研究工程师职位。